Though philosophers and the like have been analyzing arguments for centuries, a predominantly visual approach is really best for application to the LSAT. We need a reliable way to mentally map an argument without getting lost in the details.

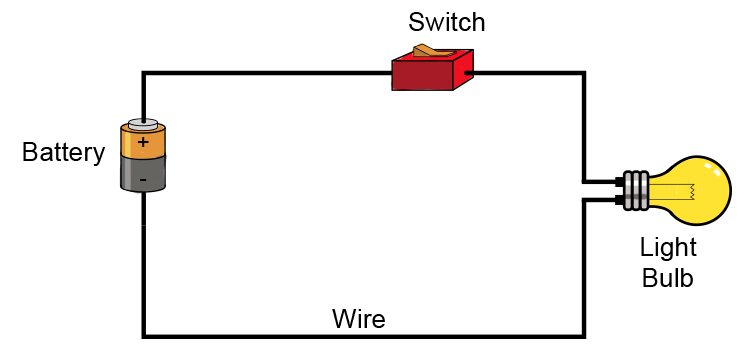

Achieving validity in a deductive argument should feel like building a simple circuit: get a small battery, attach wires to the poles, attach the other ends of the wires to a light bulb, flip the switch and…poof!

A deductive argument should be the same. Your claim only "lights up" when it's connected from one end to the other by a string of premises that line up in the right way.

Try not to think of the analogy too literally and get bogged down in thinking about batteries and wires and resistors and switches. We went down that rabbit hole and it gets complicated to the point of absurdity.

What we want you to get out of this is that circuits should be complete, connected start to finish with concepts that overlap. When they are, light bulb lights!

The Circuit

To achieve that in a diagram, let’s split the claim into Subject and Predicate. That way we can have a “starting” point and “ending” point.

Let’s put the Claim at the top, as it is the most important piece of the argument. We can split it into Subject and Predicate like this:

Now the placement of everything else becomes intuitive. Let’s get Minor Premise directly under the Subject and the Major Premise under the Predicate, reflecting those relationships.

The Qualifier should go between the Major Premise and the Predicate.

We label it here as “Modifier or Quantifier” because most often that’s the form it will take: a word that alters the claim either in quality or quantity.

Any Backing should go beneath one of the two Premises, giving the argument the opportunity to provide additional support for either the Minor or Major Premises. Remember you may not have both (or even one!) in an argument, but be prepared for them if they do show up.

Finally, the Counterargument & Rebuttal can float, attaching wherever in the argument they get addressed.

Note that we split the Counterargument part from the Contrastive Conjunction part, the thing that does the “rebutting” like “But” or “Despite”.

For now, we will attach them to the Claim Subject.

Yeah, we know, “Contrastive Conjunction” is a needlessly jargony grammar word. Sorry, we couldn’t come up with anything else other than “negative transition word” or “Switchy McSwitcherface”

Now we have our circuit.

You can imagine the light bulb sitting between the Subject and Predicate. Presuming you have all the pieces and the arrows to connect them, it should light up.

And, just as in a real circuit, the add-on elements don’t affect the light bulb. Notice what is highlighted: only the central elements. We could strip away the Backing and the Counterargument / Rebuttal and the circuit would still be complete.